I have big hands. Though, as hands go, they are not particularly long. Not of the kind that reach beyond the wrist and threaten the forearm. Nor are they so wide that they swallow other hands, offered in friendly greetings or goodbyes, whole. What they are is thick. Heavy. Fleshy. My palms crease deep and black along their head and heart lines. Where my fingers meet their knuckles the skin bulges and puckers into little dark folds of pudgy skin. No different from the doughy striations found along the back of an infant’s knees. It’s become something of joke amongst my friends, my fat hands. They particularly enjoy watching vinyl gloves, size Large, tear, split, and ultimately rend entirely to the bulk of my hands when I try to don them in preparation for handling a piece of fish. Sausage fingers is a favorite taunt. Appropriate, given the uniform thickness of my fingers and the extremely short length to which I trim my finger nails. Fireman hands is another one. Though I must admit that the correlation between my meaty hands and those of a fire fighter is lost on me. Perhaps it has something to do with the small burns and scars marbling the back of each hand.

Nonetheless, I don’t often consider my hands. Such is the case with any mild affliction. Once you’ve carried it around long enough there comes a point where you cease to be aware of it. All attentions once paid eventually fade into the white noise of life in its pacings and are ultimately erased. Of course the other truth one must be aware of when considering these minor troubles is the inevitability of that one perfect moment where this thing that you’ve learned so well to ignore is brought back into razored focus by the most mundane of occurrences.

Generally speaking, the conditions to be had along the Treasure Coast during those brilliant estival days of June and early July can be pretty goddamn great. The winds of spring have at last relented and the Atlantic, released of its harsh, foamy tumblings, turns a millpond capable of fracturing at the alighting of a lovebug. A Caribbean clarity is consigned to the incoming tide and the beachside shallows. Electrified by the summer sun, the deep is such a perfect blue that the question of whether it serves as mirror to the empty sky or the sky mirror to it must be asked. And asked again.

The fishing follows suit.

The stretch of coastline comprising Florida’s east central and southeastern seaboard boasts what is, in my estimation, the most outstanding fishery for monster snook in the country. Hands down. They pile into in the inlets by the thousands. Giant breeder snook with shoulders as hard and thick as an anvil and their bellies hung from throat to tail in a deep swag of pearly skin and scales feathered with black tarnish where the great girth of them has run along sand and stone. They hunt the estuaries and flats stretching from the fringes of the mainland to the leeward edges of the barrier coast, and they perpetually roam the miles and miles of serene beachfront troughs. Dark rangers forever seeking the small, pulsing flash of their prey.

Murderous schools of outsize jack crevalle storm the shoals of pilchards, sardines, and threadfin herring that progress along the beaches the whole summer long. Permit can be found floating at the surface high above the gentle scalloping of the undersea dunes, lazing away the long, hot hours and riding atop rock piles and wrecks, those fishy metropolises rising from the white desolation of shell and sand, with their oblique bodies shimmering like luminous dirigibles in a pale sky. And there will be tarpon. The silver titans winding their way north along the ancient longitudes of their annual migration can be found well into July swimming in schools that range from two poons to knee-buckling mobs of a hundred or more fish.

Let us not forget the open Atlantic waiting a few short miles to the east. Many of the accolades the Treasure Coast receives for its blue water fishery are centered on the sailfishing that takes place during the windswept winter months. I can tell from experience that the fishing in winter is really very good. Keep it. I’m not interested. I’ll take the summer sailfish bite any day of the week. The fish are bigger, meaner, and everywhere. Sight fishing a sailfish in fifteen of water off the beach in summer is like catching one in a martini glass. It’s just fabulous.

Look. You get the idea. The fishing is fucking good.

And in the early May of this year, schedules were aligned and a plan was hatched to head home for a few days of fishing in early July. When Nicki and I arrived our strategy would be a simple one. Tried and true. Dawn patrol would see us sightfishing the beaches, in the late morning we would attack the deep, and in the afternoon we would hunt trophy snook. All of this and there would still be plenty of daylight left for cold beers at poolside. Not bad, right? I didn’t invent the game, I just play it.

What I did not account for in my planning were the high winds that would beset and plague Florida’s entire eastern coast for latter days of May and the entirety of June. The colder oceanic waters being driven westward under the lashings of the blustery summer gales. More importantly I was unprepared for the state of general unrest in which the summer time fishing patterns would be when we arrived.

*

We found the Atlantic, upon our arrival on the Sunday of the July fourth weekend, to be in a Costanzian state of seething. Angry as an old man in a deli caught in the throes of his cold-soup fueled ravings. Sustained winds in the high teens sent pulverized scree and sea-foam whipped airborne by the tussling of waves at the wrack line against us where we strolled along the beach.

This young lady had the right idea. It wasn’t the most pleasant beach weather, so she packed up her toys and grabbed her rock and got the fuck out of Dodge. We were a little more stubborn and after finding a crest in the beach berm that kept us out of the direct line of windswept sea spray we decided to bivouac and game plan for the next day.

Ever the optimist, Nicki was solid in her conviction that as long as we were on the water it was going to be a good day. My mother concurred. I on the other hand was a little more troubled. I had been looking forward to exposing, in grand fashion, what would be a wholly new fishery to Nicki. I was also excited about the prospect of being able to get Mom on some serious fish for the first time in a long while. I briefly considered taking us west, up the Loxahatchee and out of the wind in search of resident tarpon and snook. Beautiful scenery would surely abound, but in the summer, fishing the Loxahatchee generally proves to a situation where the risk is far greater than the reward that is oft returned. Calling it feast or famine fishing would be to state the fact literally. Also taken into consideration was procuring a larger vessel from a friend and banging our way offshore, but that certainly wasn’t the right idea. In the end I decided to go old school. We were going to focus our efforts on snook fishing in the inlet with live bait. And of course there would be a few detours here and there.

With the nearshore waters a mess of windchop and breaking waves that churned like December or that treacherous strait between Scylla and Charybdis and the beachside schools of bait scattered to the four winds I was left with no choice but to catch pinfish. Tedious though the task is of catching them on micro hooks and bits of shrimp, pinfish do pay dividends. They’re about as good a snook bait as you could ever hope to have swimming in front of a bottom-heavy breeder snook. With the game plan set we put the beach spray at our backs are returned home for family time, cold beers, and old stories of fishing glories long past.

*

Dawn was an hour or more away. What lay to the east was blackness absolute. No gauzy light from the impending sunrise wrapping the secreted lintel of horizon. Not even the shapes of the palms motionless in their stands on the far shore of the intracoastal could be fathomed out of the darkness. High in the boundless vault were hung a scattering of pinprick beacons of light shining out across the void from those worlds unknowable. The oily, ringstain new moon was a dirty grey bullseye on the face of the west.

I started out across flat poured concrete deck of the marina. The gentle peel of the wheelbarrow axle flexing under the weight of its payload of cameras, rods, reels, and gear playing me along. Just before I reached the gangplank that would take me down to the good ship Sea Aperture, I stopped. The wee hours had fallen ponderous and still and there wasn’t a breath of air to be felt. Only steam and heat. I listened. Everything was quiet.

It is a favorite delusion of obsessed anglers. Those brief tranquilities in the predawn dark. You know that the wind is going to blow. You’ve seen this very thing time and again over the last twenty years. You know that the static inertia of things around you at that very moment is but a fiction to be played out under the cover of darkness. That the wind is simply sleeping. But it doesn’t matter. You show up before the sun and you watch. You listen. Movement in the trees. Wavelets in the marina basin. Anything. When these signs of the dread wind do not appear a parasitic hope flowers within you. You think, “maybe the wind won’t blow. No. It won’t. We’re going to be fine. It’s going to stay this way.”

It must be some form of arrogance, perhaps a relic leftover from the psyches of our early seafaring ancestors that remains hardwired in the minds of modern anglers, that compels us to create this false hope. It is the same mechanism that keeps us taking five, six, seven shots at a redfish that has refused us. That keeps us out past dark. That tells us to make just one last cast. Then one more. We don’t talk about it but somewhere deep down inside of us we believe that our puny human will is enough to countermand the verdicts of natural law. Wind. Rain. Clouds. Stubborn fish. We will fail 999 times. We will fail 1,000 times. It doesn’t matter. We’ll always talk ourselves into that false hope. Because on the 1,001st time that we’re standing there beneath that black pitch summoning a windless morning in spite of the forecasted breezes and the wind actually doesn’t blow we want to be able to look over at the person we’re fishing with and say, “See! I told you the fucking wind wouldn’t blow!”

So, in the hazy, yellow candescence falling from the security lamps atop the marina barn I started at rigging up for the day. A Bimini twist here and there. Swivels. Flies. Files and hooks. A few clinch knots. A Homer Rhode. All the while keeping an eye fixed on the flag, a dim attenuation incising the dark heavens where it hung limp against its pole at the mouth of the marina.

By the time the sun crested in the east the wind had also risen. It sped along at a quickly stiffening easterly clip. It’s a fairly short run, only a couple of minutes, to the grassflat-cum-pinfish wonderland that over the past two decades has provided ample quantities of the delectable little baits when I’ve required them, and by the time I arrived the wind was already threatening the low and mid teens. After the momentary disappointment and accompanying head shakes at my failure to bend the weather to my desires, I deployed my chum bag, put the Pretenders on the stereo and got to work. If you were unaware, pinfish love Chrissie Hynde, and by the time Up The Neck started the small black shapes of them were scrambling about in the slick. Along with a few particularly gorgeous mangrove snapper.

One by one the pinfish came over the rail and with the livewell a blacked out, churning danger of hypodermic dorsal rays I pulled anchor, motored back to the marina and picked up Mom and Nicki and off we went.

*

The tide was just beginning to turn. A small gulf of a few hours lay between us and that particularly sultry stage of outgoing tide that sees those big inlet snook getting all hot and bothered and hungry and I still didn’t have much of a plan for the morning. As we moved towards the inlet, tailing’s of that mornings incoming tide were still continuing to push clean up onto a narrow section of sand flat that boasts a pronounced edge and close proximity to deep water. It’s an area that, when the water is clear and high, can serve as a sort of lazy country road to some absolute stud snook as they make their way towards the inlet. It’s not always a guarantee that they’ll be there, but the sun was up and the water was still moving.

It’s a bit of a tricky proposition attempting to get skinny in a center console with a V-hull. No pushpole. No trolling motor. Basically, you stick your nose up onto the edge of the flat and drift until your about to bump bottom. Then you fire up the outboard, slide back out and start again. You’re at the mercy of wind and tide. Lucky for us, I had spent enough time as a teenager putting the Sea Aperture in dicey situations to have a good feel for exactly how to set us up on a drift that would allow for a maximum distance to be covered. It’s sight fishing in a perfect vacuum of technical maneuverability. Exciting. I guess.

I jockeyed the boat onto the line that we would take up onto the flat and explained the situation to the ladies.

“These fish are all going to be moving towards us. Right up this line.” I motioned with both hands up the midline of the flat. “The shots are going to come from 1 to 4, maybe 430ish. Good?”

“Yep.”

“Got it.”

“Alright. ”

I climbed up onto the crow’s nest atop the console and started idling up onto the flat.

Maybe I was still half asleep and in need of another cup of coffee. Maybe I was distracted by the paddleboarder in the safari hat, face waxed with white zinc oxide, charging up the flat at us. Maybe it was the sight of the wake coming off the chines of the 50-foot motor yacht steaming full-bore out of the north . Maybe I’m just a fool. Whatever the case, I just cut the engine and started the drift. I neglected to tell the ladies that we had arrived. That we were fishing. That we were on the flat and that we could see fish at any moment. Like, right now. I was standing there sipping my coffee like an asshole watching Nicki set up her camera so she’d be ready in an instant to capture any moment and my mom on the phone with my father, eager to learn if we’d caught any fish in the eleven minutes since we’d left the marina, thinking, “what the fuck are they doing?” Then I looked up.

“Shit.”

What I felt in that moment, staring down the flat, was very similar to how I often felt at about 16 years old when cones of yellow police flashlight would come sweeping up the boardwalk, or through the woods, or around the corners of the parentless house just as the party got out of hand. It was fear. Primal. Simple. fear.

A pair of snook, both easily fifteen pounds, were coming in at 1 o’clock. They were at fifty feet and closing.

I jumped down from the console. What was left of my coffee exploded off the dash and soaked the front of my shirt. I drew a spinning rod from the rocket launcher and by the time I made the bow the fish had closed the distance to us by about half. I let the soft plastic fly. The line was right, but trajectory was horrible. The bait hit the water where it should have, but came in so low that it skipped like a stone right over the fish.

Roiling water and twin tornadoes of silt told the tale of how well those fish had received my panicked cast. Even worse were the stares that awaiting me when I lifted my eyes from the water. Glacial is a word. It gets us about halfway there.

“Shit.”

There was the fear again.

*

After being verbally chastened for my poor captaining and angling abilities, deservedly so, we regrouped and got back on the drift. Schools of sheepshead barred black and starwhite roved beneath the mangroves in water so clear that you could see the draw of their gills at seventy feet. Not a snook in sight. A second drift along the flat revealed nothing more than a lone Bud Light bottle steering along in the tide at the edge of the flat. As we neared the end of a third drift a bank of clouds rode before the sun and threw a white sheet of glare across the last third of the flat. It looked as if I had squandered the one opportunity that this flat had been willing to offer.

Then I saw them. A hundred-fifty feet out coming from the mangroves on the far side of the flat. Two fish. Both on the plus side of twenty-five pounds. Relaxed and bumming across the sand. Black as a pair of manatee pups.

“You’ve got two fish coming in. 2 o’clock. You got ’em?”

“No.”

“They’re big fuckers. Coming straight in .”

“Should I cast?”

“No. Wait till you see them.”

Nicki strained to see through the glare. Heavier and harder to cut from her low angle.

“I don’t have them.”

“They’re at like ninety feet. Just wait.”

The fish swam into the glare and broke apart into indeterminate shadows under the harsh light.

“Where are they?”

“Just wait. They’ll show. They’ll show.”

The fish had turned and when they came out of the glare they were swimming parallel to us. I heard my mother gasp behind me.

“Fifty feet. 3 o’clock. In front of you.”

Nicki swung her rod to 3 o’clock. The fish at the rear had begun to turn off and was tracking away from us. The lead fish kept moving.

“Right there.”

“Got him.”

“Cast.”

I saw the whole thing from the tower.

Nicki made her cast. With a barely audible hiss the shad tail split a slick tidal meniscus boiling a foot and a half beyond and beyond and a foot and a half before the face of the lead fish. With a single sweep of its tail the snook drew to a dead stop. Her flanks lit up. All seagreen and sparking with silver. Her dorsal and pectoral fins flared and flushed golden like evening primrose in bloom. In the streamlined hollow of her skull the jade eye shot through with an obsidian ovoid torqued slowly as it dialed in on the small translucent body in its steady advance.

The snook swam her tail once more and eased up on the bait. Only a few inches away. She stiffened.

And in a rush of water and alluvium she gone. Charging north up in the intracoastal and taking her companion along with her. I cried out. I clasped my hands over my heart to in an attempt to stifle the basic drumming in my chest.

Nicki’s arms hung limp at her side. Her shoulders slack. The spinning rod twisted in an uncertain balance at her finger tips. She was staring after the snook. Now long departed.

“What did I do wrong?”

Her eyes still hadn’t lifted from the water.

“Wrong? Nothing. That was a perfect cast.”

She reeled up the slack braid and stowed the rod. As we made our way towards the inlet everyone was quiet.

It occurred to me later that day that the problem, or what she did wrong, if you can call it that, was the cast. It really had been perfect. Exactly where it should have been. That fish should have crushed the bait. The eat should have gone off like a hand grenade in a pickle bucket. It should have been violent and awesome. But the fish refused it. Outright. Make all the bad casts and bad presentations you want. Spook the fish. None of that hurts as bad as when you do everything right, the fish responds, and ultimately thinks better of it for whatever unknown reason and just swims away. The stakes are too high. Anything other than an eat is ultimate failure. It hurts too much. At that point all you want to do is break the fucking rods, throw them in the water, crank up and go the fuck home. It’s enough to make you want to quit fishing. Forever.

*

The tide had still not begun flushing out hard enough to start fishing the live baits. We started for a spot in the inlet, and if you’ve fished Jupiter Inlet you know exactly where I’m talking about, that is notorious for holding wads of under and mid slot snook. As we approached the snook holding structure in question, one of the area guides, with a pair of clients on the boat, was coming up behind us with the same idea that we had. The captain at the wheel of the little blue skiff is a friend and one of the nicest people and best fisherman you could ever hope to meet. He’s a gentleman, humble, and would give you the shirt off his back if you asked for it. He’s one of the good guys in a sport that needs as many as it can get. Needless to say, I pulled back on the throttle and let him go ahead of me. He offered to let me slide in next to him, but I declined, as there was no need to crowd in on a Monday afternoon with not another boat in sight. I moved us off to another nearby flat to do some blind casting until the tide was right.

We watched, within fifteen minutes of our departure, two boats pull directly into the spot and anchor a little more than a boat length off of where my friend sat at anchor chumming the snook. Both new boats carried young fisherman. They made it a point to cast into the lines of my friend’s anglers, even when they were hooked up. At one point the anchor of an offending boat pulled and the prop of their forty horse Yamaha nearly went through the prow of my friends boat as they drifted back, unaware of what had happened. After some pushing and pulling they managed to slide past without collision. Rather than moving along and counting their blessings that no harm had come to either boat and that their carelessness had earned only a gentle chiding and not something much worse, they just reset their anchor. Even closer this time. Like nothing had ever happened. I also watched these same kids catch a snook. The fish was maybe twenty-six or twenty-eight inches long. Rather than landing the snook carefully, removing the hook, and releasing it quickly, they tried to net the fish with a bucket. A bucket. You could hear the fish rattling his head against plastic from across the inlet. He’d flop out and they would try it again. They attempted this five or six times. Finally, one of them bailed the fish into the boat. They chased the snook around the deck for a moment or two and finally managed to catch it a second time, at which point they got the hook out and just flipped him over the side.

It was sad to see such a lack of respect accorded to the other fisherman already in position and fishing. It doesn’t matter who’s in the other boat. Guide, recreational, TV personality, or mortal enemy. You don’t cannonball someone else, you go and find your own fish. It’s just good manners. Or rather, it’s being a good fisherman. What really bummed me out though was their technique in handling that snook. Which is to say they had zero regard for the well-being of the fish. It was just a thing that had come aboard. Not a beautiful wild creature. And they’ll probably keep handling fish like that for the rest of their lives. Though I wanted to task these kids to task, I kept my mouth shut. It probably wasn’t even their fault. The stupidity exhibited was atypical for teenagers. They probably saw someone who should have known better doing the same thing and assumed it was okay to behave that way. It’s a bummer, but unfortunately it happens. Lucky for these kids though there are angling communities, like the one we have here at SWC, that foster respect, education, conservation, and general good times. Hopefully they find us and wind up being better people and anglers.

*

When the tide finally did hit the right stage, we got on the drift and deployed pinfish.

It takes two or three drifts to really dial in where the snook are concentrated and what drift line makes for the best presentation and ultimately, the most eats. The first three or four drifts did not result in any hook ups, so I moved us around and tried a few different lines. Our baits seemed to be a little unnerved here and there, but we were still without an eat. I wasn’t worried at this point, just a bit perplexed. We should have come across at least one wayward snook at this point. Yet we remained empty-handed. I moved us around some more. Started in different places. Made short drifts. Made really long drifts. By the time we had been sucked down the inlet for the dozenth time without even the first eat I found myself in the middle of a what-the-fuck moment. The fish weren’t getting pressured. We were the only boat on the drift. Low salinity wasn’t the issue either. The water was plenty salty. At the surface, the water temperature read only a degree or so colder than what it should have been, but certainly not enough to shut the fish down. Inspection of baits and lead recently returned from the bottom did not betray any thermocline hiding in the lower depths of the shallow water column. I considered moving outside of the inlet to fish the jetties, but with the seas on the outside heaving and bursting against the rip-rap every few seconds the option of seeking out an oceanic school of linesiders was out of the question. As such we were left with little choice but to keep trying.

After a few more fruitless attempts, Mom handed out her rod to me.

“Here. You need to try.”

“Nah. They’re gonna eat. Stay with it.”

“Nope. I think I’m bad luck.”

Nicki looked over.

“I think I’m bad luck too.”

I acquiesced and took the rod from mom.

“Fine. I’ll fish.”

I motored us back up to the top of the drift and fired the smallest pinfish we had in the livewell, about the size of a half-dollar, into the drink. The tide caught us and we started floating east.

On the seawall lining the northern face of the inlet there is a divot. A pit in the stone stained by time, water and weather to a dark, muddy brown. A small cavity that surely goes unnoticed by most. Though over the years I have found it to be a rather useful landmark and drawing parallel to it usually means that the baits are firmly embedded in a hostile and deadly LZ.

I watched the seawall as we slid along with the tide. In short order the Sea Aperture drew even with that subtle landmark.

“Watch this, mom. I’m going to get an eat right…now.”

A heavy thud telegraphed up the monofilament and the line swung tight. I set the hook. The spinning rod doubled. There was some head shaking. Some bull dogging. The ring of the drag in its turnings. It was a neat trick and without it I’m not sure that the first snook of the day would have ever come to hand.

While this fish offered us a few moments where it seemed that providence would finally smile upon us, it was short-lived. We were unable to manage even one more eat while the tide was still moving. As the water slowed and approached slack tide we packed up the bait rods. We were beaten, but not done.

We changed gears and moved to an area that on low water and a slackening tide gives up sight fishing opportunities on fish moving up from deeper water. I still hadn’t really put a solid bend in the 8-weight Colton I’d purchased a couple of months prior to this trip and this seemed as good a chance as any to do it.

The Lightsaber Pilchard from 239Flies seemed an apropos choice given the amount of small threadfin’s meandering about the tideline. Off the reel came fifty or so feet of floating line and then we were just waiting on the snook. It didn’t take very long. The first half-dozen snook to which I presented the fly met it with lazy glances and very little curiosity. Not even a second look was offered. I adjusted the presentation. A little more lead and a slightly longer, sliding action on the strip and managed to get two fish to turn, but neither would commit. A larger fish, one in the mid-thirty inch range slid up onto the flat. Floating high and at the edge of color change, back charged with the umber tannins of loamy river bottom and steeped mangrove roots. He was maybe eighty feet out and not moving at all. It was a longer shot than I usually like to take, but I wasn’t moving to him and he wasn’t moving to me, so I peeled off the extra line and sent a loop after him.

The fly landed soft and on the mark. I let it settle. Two short strips got the fish to turn. Another strip and the snook pushed hard on the fly. Gills flared and jaws yawning wide she swept at the fly. Water boiled. But she never found the steel. I stripped again. She followed again. A last strip. The fish turned away and swam higher onto the flat. The yellow half-moon of her caudal fin swaying just above the surface.

Asshole.

I had another few shots at the finicky snook, and these were returned with more half-hearted, bullshit attempts to eat. I was unhappy. Very unhappy.

We conceded the daylight the hours and headed back to the marina. An interlude of cold beers seemed the best way to wash off the frustrations of the past few hours as we weren’t quits just yet. There was still the evening tide and nocturnal snook to be reckoned with.

*

This is about as close as we would get to any nighttime snook. We should have arrived to a steadily moving tide, with another two hours of flow, sucking out beneath the lights that I’d chosen. What we found was stagnant water. The outgoing had proven too weak to get the water really moving in the intracoastal. The fish were certainly there. Swimming easily and carrying on with their own little disco party in the honed, chemical light of the halogen bulbs studding the dock ends. Not a single snook fed on the tiny translucent morsels scuttling about the barnacled pilings or bounding whitewashed in the lamplight at the shadowline. Nor could one be coaxed into feeding. And I threw the entire box of flies at them. Soft plastics too. In the end changing venues in search of moving water was thwarted by high black buttes of electrified thunder head, crowns crushed flat against the jet stream and seeping into the black east like water spilt, that rode the horizon to the north and south of us.

Well, I guess we did get fairly close.

*

The next morning we woke to find the firmament bossed with the remnants of the thunderheads we had encountered the previous evening. Grey crags of rain cloud lay in random scatter about the east. A stormy minefield punctuated with downy knots of white cumulus. Checking the radar revealed that this slipshod squall line rode all the way west into the Gulf and east to Walker’s Cay and far beyond. Though it wouldn’t be enough to keep us off the water, it would be enough to get us wet.

We made our way to the marina to hook up with dear friend and former Major League hurler, Bill Gullickson. A second pick overall in the 1977 MLB draft and a 20 game winner for the Tigers, Bill is one hell of a baseball player. He’s also one hell of a fishy dude. With the wind settling he called me that morning inquiring as to whether or not Nicki and I wanted to join him on an offshore trip. With a considerable amount of blackfin tuna in the area, the beaches still a mess, and the snook fishing in the toilet, it seemed we were in a blue water or bust situation.

We cleared the inlet shortly before sunrise and headed east. Though the majority of our day would be spent trolling, we made a brief pit stop to acquire some live bait that would be soaked later in the afternoon.

A half-dozen blue runners and a pair of sardines later and we were moving again. As we ran southeast Bill and I explained the basics offshore trolling to Nicki. While she is getting very good at hunting fish in the skinny stuff, Nicki is very much a neophyte to the world of offshore fishing. We started small. Keep your eyes peeled. You never know what you might see out there. When you’ve got a fish hooked keep the tip up and line tight. No slack. And most importantly start drinking beer before 9am. Nicki ended up being a natural.

We swung the bow to the north, set the lines and got to work. The first hour passed slowly. There was nothing to be seen in the way of weed, rips, or edges. Not deterred, we held our line. In the blue water arena I find that patience is paramount. A willingness to stick to your game plan and to fish carefully without moving or changing tactics too quickly generally pays off. And it did for us. The first tuna came over the rails just after 9am, pinned to a blue and white jet head we’d been towing 200 feet off the stern.

We made a long, wide turn and trolled back through the area. It can be difficult to target these open ocean ramblers when there is little evident structure on which the fish might hold. You’ve either got to be lucky, or good. Or maybe it’s that you’ve got to be good to get lucky. In any event, be it the chicken or the egg coming first, we worked hard, all the while keeping close eye on the temperature gauge. And after about forty-five minutes of fishing we picked up on a seam of slightly cooler water that appeared to be running adjacent to the line we were fishing. We adjusted our tach and trolled in long zigzags across the temperature variation. Ten minutes later the jet head got smoked again. This time it was Nicki’s turn on the rod.

Often, the conventional tackle necessary for most offshore fishing situations can be a bit cumbersome for a first timer. It’s heavy, gimbal butts hurt, the drag systems are different, etc. But I do have to say to that Nicki handled it like a pro. And it yielded her a tuna on her first day out. I think it took me about four years to catch my first blackfin.

There’s also something to be said for the twangy pop and crackle of fresh monofilament being spilt from a conventional drag running in reverse. It lets you know that you’re in a fight. With chances of the heavier mono separating slim and structure that would give the fish opportunity to cut you off non-existent, your only way out is to whip that fish’s ass.

After another half-dozen fruitless sweeps of the area we moved on. Around noon we had our third knockdown of the day. A small barracuda who had thought better of hanging out in the safety of the inshore shallows and decided that braving the deep would better suit his chances of survival.

By the time the afternoon rolled around we’d finished all the beer. The offshore bite had fallen into a fishless inertia and the desire to reignite our angling fire was high. We moved inshore and switched over to the live baits. The idea being to get tight on some solid kingfish and get Nicki another notch in her reel seat. It didn’t happen exactly as we’d planned. The kingfish, perhaps a bit lazy with the sun still so high, never paid us a visit and once the bonita found us our baits were cut down in short order. No matter though. Say what you will about the false albacore, but there is positively no denying that they are about as much fun on light spinning tackle as any other fish that swims.

With our live bait supply shaved in half and the explosions of feeding bonita general at all points of the compass, we got out the top water plugs. The method is fairly simple. Cast the plug as far as possible. Twitch. Twitch. And hold on. If the fish misses the plug, which happens most of the time, it becomes a really exciting game of keep away in trying to retrieve the plug all the way back to the boat without it being eaten. The goal isn’t necessarily to catch the bonita. Rather it is to drive them fucking insane.

We were treated to twenty minutes or so of absolutely epic eats. Plugs being launched fifteen feet skyward. Fish breaching in an attempt to eat the plug. Other fish trying to steal the plug from the mouth of those already hooked. Absolute chaos. After two relatively slow days of fishing there is no better medicine than furious, violent topwater action.

By the time Shark Week showed up Nicki had been long beset by the humbling effects of fiery forearms, cramping hands, and the uncontrollable urge to keeping casting into the fray. Ill advised though it was, we did manage to land a last tunny in the midst of being laid siege to by the terrible menagerie and their doom dealing.

I will concede that my knowledge of shark species is cursory. But, I believe the above is a Caribbean reef shark. In addition to this guy and his homage to Spielberg’s best film, we also had a hammerhead in the 9-10 foot range orbiting us in an ever tightening circuit, and all the bull sharks.

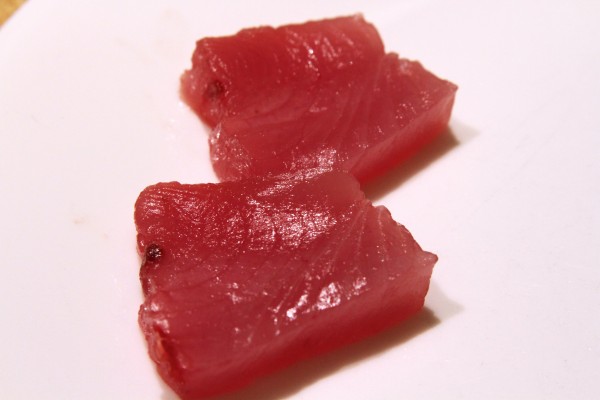

Enough blood had been let in that short hour and a half to satisfy a few days worth of entertaining sharks. With sore arms, plenty of laughter to play us home, and fish still to fillet we called it day a well spent. And once the tuna had been butchered and plated the evening served us rather well too.

*

That evening I sat on the edge of the bathtub in my ancestral home, hands in my lap, studying them. They hurt. A touch of swelling had taken hold in them. My knuckles whited at their bases ever so slightly when I balled my hands into fists. There were small red cuts on my fingers and palms. Broken skin. Chaffed skin. A band of pink sunburn rode the back of each hand. I turned each one over. Left and right. I held them up to the 70 watt bulbs. I even smelled them. Sweet with brine and fish slime. My appraisal was not due to any surprise at the state they were in. In fact, it was quite the opposite. I had expected them to look this way.

It was my lack of surprise at the poor state of my hands that told the story of their fatness. They’d been shaped, and made chunky in the crucible of the very fishery we’d been enjoying the last two days. Twenty years of tying knots, twisting wire, learning to throw loops, sticking myself with hooks, filleting my fingers, leadering fish, fighting fish, and of course setting them free. All those tests and time before I was even old enough to have a legal drink. Every callous and little episode that left them sore, stronger, had kept.

So I’m stuck with these heavy hands, built by and better suited to the rather coarse business of bait fishing and battling fish on heavy tackle, that now look so very out-of-place as they inform with 8 and 10 weights the fine, precise lines so very necessary to the delicate art of fly fishing that currently consumes such an enormous part of angling heart.

Perhaps my fat hands born long ago and now so at home gripping the cork of a fly rod, also betray an essential truth about fishing. It is perpetually dynamic. For those who love the sport, fishing is a constant evolution of desires and styles and fulfillments. The charms and fascinations of fishing change as we change. The quarry, the places, the systems, and the techniques. None of it remains the same. We require this of the sport, and it delivers. Fisherman are seekers inexorably pulled to the farthest corners of the earth in search of what we love. And to the very last one of us we will go in search of it. But that’s only half the story. That’s how it ends and it is not what makes the story beautiful.

What makes our story as fisherman beautiful is where it begins. No matter the changes that come over us or how long our coattails may fly in the wind as we drift so far away, there is always that one place where it all began. Where we come from as anglers and may always return. The old stories live here. The lost fish. Old friends. Spectacular catches, undeniable. That place to which you’ll never be a stranger. Where you float before a fiery sun, empty water, and breaths of wind a gentle choir. Your thinking is always clear here, where hooks have set and drags have run. Where the promise of fish is always calling you. Where you are home.

—

A note about the title:

Caledonia is the name given by the Romans to what is now Scotland.

In 1977 Dougie MacLean penned the song “Caledonia,” a folk ballad that sees the narrator reflecting on his youth in Scotland. I have never heard his version. As such, I would like to offer special thanks to good friend and incomparable vocalist Roisin Byrne for giving me a copy of her astonishing a capella cover of “Caledonia.” It proved to be just the right nudge I needed to complete another blog post that is FAR TOO LONG.

-Baz